a personal relationship with literature

discovering ourselves in fiction

Why do we read fiction? There are many superficial explanations we could offer: for the pleasure of stepping into another world, the opportunity to better understand the human condition to which we all are subject, or a chance to peek into another’s mind.

All these are valid and good reasons—I don’t think there’s a bad reason for reading literature, even if it’s just “to look worldly in public.” We all do performative things at times; might as well do something performative that also enriches the soul.

But I’d offer that there is another reason we read literature, even if we are not quite aware of it. I’d offer that this motivation is exactly what helps us differentiate between “good” and “bad” fiction, and is the source of that vague feeling of dissatisfaction when reading a not-so-great book. What we are seeking is something small but resonant: a personal identification with symbols.

symbols in the world

The type of symbol I’m talking about here is not your generic sort of symbolism e.g. “the blue curtains symbolize the character’s depression”. What I am more interested in here is the personal symbol, which I would connect to Jung’s theory of synchronicity. So let’s go there first, first to synchronicity, and then back to the symbols themselves.

A synchronicity, in Jung’s definition, is an external event that matches an internal state1. A rather basic example from my life is that my favourite number is 23, and I find when I feel I am “on the right path”, I tend to see 23s everywhere. A more striking example is that when Jung started focusing on a particular figure in his imagination, associated with the kingfisher, he found a dead kingfisher on the shore of the lake near where he lived. That area was not known for kingfishers, so it was a striking coincidence.

Now, the obvious objection to this is that it’s mere confirmation bias, or a cognitive distortion, or just simply coincidence and nothing more, etc etc. For the purposes of this essay, it’s not necessary that you believe synchronicity is real2; we can accept a much milder definition of “sometimes, things happen in the external world which reflect what’s happening within us.”

But whether or not a synchronicity is “real”, it does feel significant. It feels like a wink from the universe, or from God. It imbues a moment with a personal meaning which, while small, leads to a sense of self-recognition.

symbols in literature

We could say that a synchronicity is a “meaningful reflection of the Self out in the world.” In literature, then, a personal symbol would be a meaningful reflection of the Self in the text. We see ourselves in the text, if just for a moment. It is the same effect as when a song lyrics seems to pierce our soul: “ah yes, that’s how I feel, that’s it.”

But why I think this is significant, and why it goes beyond just a moment of “I feel seen”, is that such personal symbols can often bring an unconscious idea into consciousness. For example, when I see a 23 figured prominently, the thought “perhaps I am going in the right direction” leaps into consciousness, whereas before it might have been in the background. Similarly, something that stands out to me in a book might bring an unconscious realization “into the light.”

A symbol is thus not just a reflection of what we already know, it’s a reflection that brings something unconscious into conscious awareness.

surfacing the unconscious

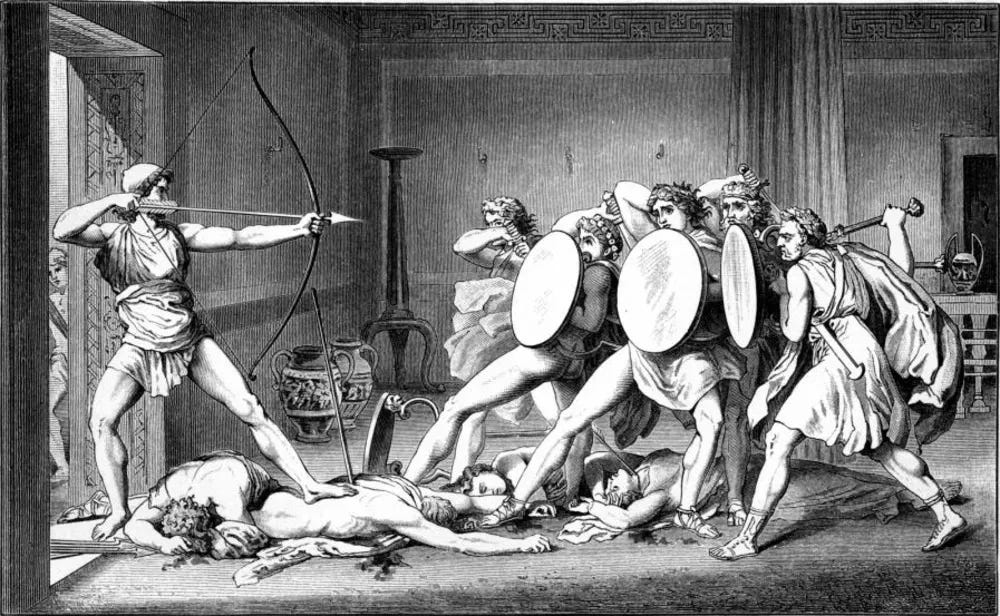

I recently wrote about how I first read the Odyssey in my early 20s3, and I felt enormously impatient with the “homecoming” sequence. For context, at this point in the text, Odysseus has been away from home for 20 years, and his home has been taken over by a bunch of nasty folks trying to seduce his wife. He’s finally returned to take back his home, and the implicit promise of the text is that there’s going to be a big climactic fight.

But that’s not what happens, at first. There’s a long sequence where Odyssey is disguised as a beggar by the goddess Athena, and enters his home and bides his time, waiting for the right moment to strike. As he waits, he has to endure insults from the suitors, and he has to see his long-missed wife without being able to tell her who he is. It’s quite agonizing. One is dying for Odysseus to finally draw his sword and get to work.

This sequence stuck out to me then, in my early 20s, but I didn’t think too much of it then. But I’ve recently been going through a phase in my life which I’d call a “humbling” period, where I’ve had to really grapple with what my ambitions are and how long it will take to achieve them. During that time, Odysseus came back to mind.

What bothered me about that homecoming sequence, in retrospect, was the fact that Odysseus has to submit to humility to such an extreme degree, putting aside his pride and impatience… which was exactly the thing I was wrestling with. But it was reflecting on the Odyssey that helped crystallize that for me: “ah, what I am struggling with is humility.” I saw myself in the text, in a way that made me aware of my unconscious problem.

the benevolent mirror

We can thus say that literature can function as a benevolent mirror, reflecting aspects of ourselves back at us, through these symbolic moments4. I would go so far as to say that when someone complains that a book didn’t really “land” with them, they mean that they didn’t see any of themselves in it, consciously or unconsciously. There’s nothing wrong with that (not every book needs to be for everyone), but it does say something about why the classics are the classics: they speak to many of us across the expanse of time.

I call literature a benevolent mirror, but the process can be quite uncomfortable. I think that’s why we have a slight bias to view reading great books as a “noble” activity: not only is it sometimes technically difficult, but it also requires us to confront unconscious parts of our psyche.

collecting symbols

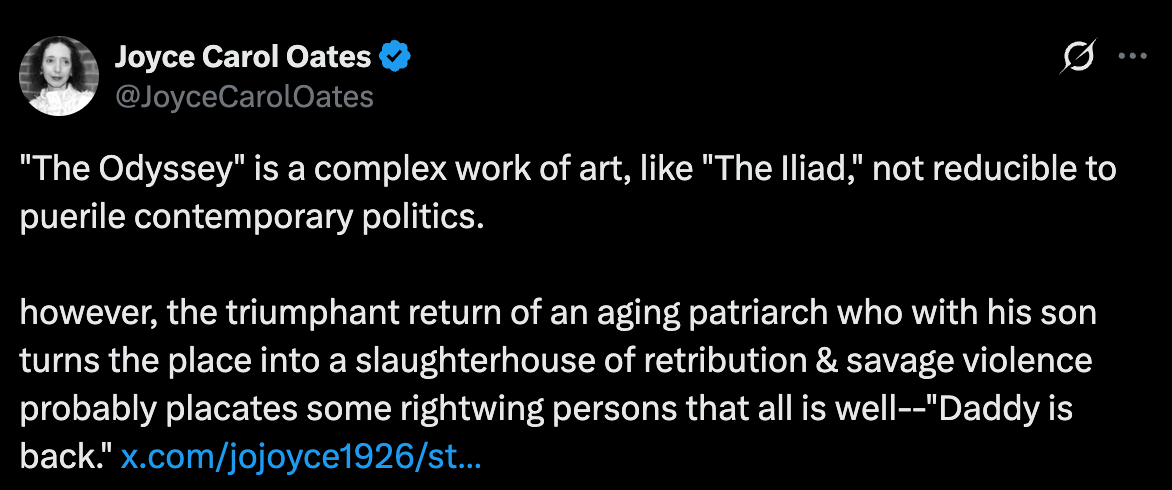

Not that everyone submits to the process. I loved this take from Joyce Carol Oates about how some commentators use the Odyssey as a normative patriarchal story, as a source of comfort. The text is showing them something in themselves, that they are attached to the idea of the patriarchal “daddy” but they are not yet conscious of it.

But we can’t blame them for that, because we all do that (indeed, my own experience with the Odyssey is not so far removed from this framing!). The symbols we encounter in literature take time to ferment. They rest in our unconscious, and then emerge when the moment is right. Odysseus sat in the back of my mind, dressed in rags within his own palace, until he last emerged again over the past year.

Reading a lot of books, then, is not for mere pomp. It is to collect a storehouse of personally relevant symbols. It is to read a book and say, “I saw myself in that, but I’m not sure how”, and to let that sit for ten years until you finally say, “Ah, I see it now.” It is a process of noticing our own discomfort and our own resonance, and pause for a moment and ask what that’s all about.

Reading literature is a process of seeking ourselves in the world. We are still bound by the commandment of the Oracle of Delphi: “Know thyself.” When we submit to the process of reading literature, when we allow the symbols to work on our unconscious, then it can become another way to bring the hidden aspects of ourselves into the light.

Jung would emphasize that a synchronicity is a meaningful coincidence with no apparent causal connection: the outer event aligns with an inner image, even though there’s no apparent way the inner image “created” that event.

“Synchronicity is hellishly difficult — terribly difficult — because the moment you try to grasp it conceptually, you find yourself slipping either into primitive magical thinking or into the rigid framework of classical causality. Neither is adequate. The real challenge is to hold a position beyond both, where you can acknowledge the reality of acausal events without falling back into superstition or violating the principles of modern physics.” - Marie-Louise von Franz

Coincidentally, at the time of writing, this tweet has 23k views.

The text could also be reflecting collective patterns such as archetypes, which often have a similar “striking” effect.